As published in Classical Singer, September 2008

Much like that wonderful line from The Princess Bride, “Hello. My name is Inigo Montoya. You killed my father. Prepare to die,” I warn you. As we begin the discussion of retiring from professional singing, prepare to be wounded.

It is achingly difficult to think of giving up something in which so much of our love, so much of our passion, so much of our self-definition—and so much of our ego—is wrapped. What I write here are my subjective observations and feelings, of course, because the only singer with whom I have 100 percent experience is Adria Firestone.

You’ve heard of her haven’t you?

“Who is Adria Firestone?”

“Get me Adria Firestone.”

“Get me a young Adria Firestone.”

“Who is Adria Firestone?”

This series is about the last two lines of that progression: Do you recognize the signs? Is it time for a career change? How do you deal with the grief and the mourning when a career that has defined you is suddenly, or gradually, taken away? What else is there? How do you come to be at peace with saying goodbye to a part of your soul?

Have you ever felt that gong of truth go off in your body? Have directors been treating you differently? Have you been offered different types of roles? How has it felt?

Words from CJ Williamson, Classical Singer’s founding editor

Back in 2004, in Connecticut, at the first Classical Singer Convention, I met many singers: the starry-eyed novices; the practical working singers; the singers who were clinging to 20-year-old demos and headshots, still questing for the elusive break that would surely make their career; and finally, the group of singers who had made their mark and had a successful career in the past. It seemed even the latter were divided into two camps: those who spouted entertaining stories and peppered every sentence with important names, and those who knew who they had been and who they were at the time of that Convention, and sincerely wanted to find better ways to communicate their experience to young singers.

I didn’t fit comfortably into any of these categories. I felt such a deep sadness and couldn’t grasp the why of it. I needed to understand something, and I didn’t yet know what. Now, I know my own wound was too new. I didn’t have the perspective of distance and time. CJ Williamson, the founder and longtime editor of Classical Singer, saw it. Soon after, she sent me this e-mail.

“I was thinking about you the other day. Your face keeps coming to [my] mind—the time I ran into you as you were outside the hotel; you just had such a poignant look on your face. It has haunted me. . . . I thought I would ask you if you would ever care to explore in words the experiences of singers as they contemplate retiring from singing and finding new paths.

“The pain of that thought. The liberation of that thought. All the ramifications. Saying ‘no’ to a job offer for the first time. Having to watch as younger singers take the jobs you used to get, and gulping as you realize that it’s their turn. The rage of ‘But I wasn’t done! I’ve still got more to say!’

“Because it’s taboo, singers suffer in silence when it’s time [to retire]. . . . They don’t know how to do it. It’s like dying with no one telling you where the hospital is. I’ve been wondering if you could be the one to lead the crusade here.”

CJ expressed it so beautifully—and at last, dear, inspiring lady, I’m taking up the gauntlet.

Saying goodbye to an old friend

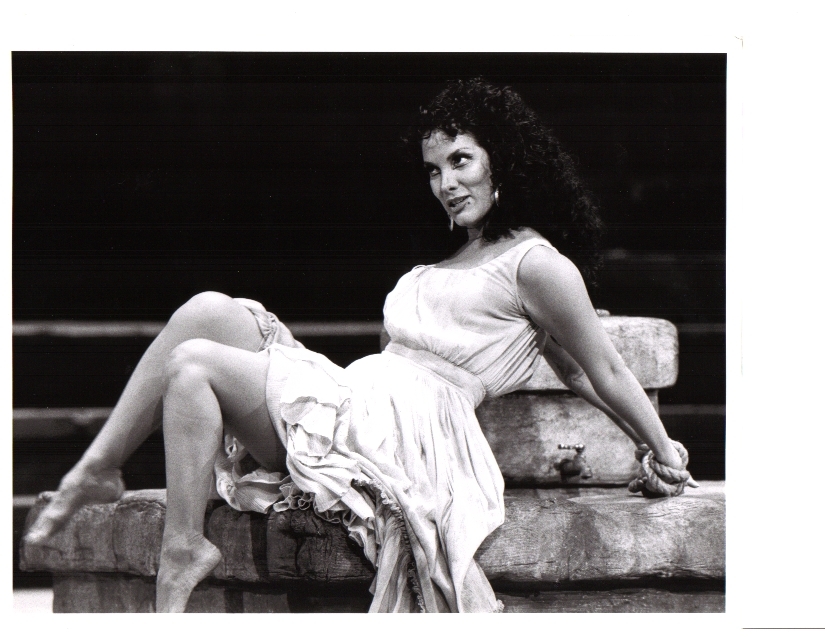

The first time the gong of truth went off in my body, I was backstage in Córdoba [Spain] doing yoga, as I always did before my first entrance as Carmen. I was aware of a quiet voice that said, “This is the last Carmen you’re ever going to do.”

I was stunned. I wondered whether I would be able to get through the performance without sobbing. Thankfully, the seasoned pro took over and I gave my performance, but part of me was an observer, and I knew I had experienced truth.

That was a tough realization. Carmen and I grew up together. She put food on my table and a roof over my head. Her strength protected my softness, but now I had become the woman of Act 4: “Libre elle est née, et libre elle a mourra.” At last, I belonged to myself—but what exactly did that mean ? I had been on stage since I was 10, modeling from age 5—what else was there?

Heeding my own voice: body, mind, and spirit

Just two years prior to the CS Convention, I performed the role of Desirée in Sondheim’s A Little Night Music with Utah Opera. I found a deep kinship with this character, who was living “The Glamorous Life” (the only number in the show I disliked—I guess it was too close for comfort), dashing around the world, performing, receiving applause and critical accolades, returning to solitary hotel rooms, and briefly returning home, where not even a plant, or a pet, waited. Many of my colleagues sublet apartments in the city. They didn’t see the point of enduring the expense of keeping their own place.

I never had the strength for the idea of “anywhere I hang my hat is home.” I needed one place on this planet in which I knew where everything was, a place where I could feel an “ahhh” of relief when I opened the door. I needed a place where I could dump out the suitcases, run out and get my hair cut, get a facial to remove the stage makeup, squeeze in my yearly physical (or not), fly by the dentist, and pick up my dry cleaning—a place where I could pack the suitcases again and start my run to the airport. While I waited, in the same airport—after a while, they are all the same, I promise you—I tried to keep my friendships alive by calling all over the world, keeping track of time zones so I didn’t wake my friends at 3 a.m., or by sending e-mails. All of us become experts in using downtime, don’t we?

During that production of A Little Night Music, I was again possessed by a deep, bittersweet feeling that it was time to say goodbye to my beloved stage. I had seen the world. I was exhausted with travel. I had gained a lot of weight. I had lost my father, my mother was ravaged by Alzheimer’s—and I had lost the lust to perform. The public adulation and the exotic locales no longer satisfied that nameless longing. I felt old, fat, tired, and world-weary. The refuge of the myriad of characters I portrayed was no longer enough. I needed to uncover the part of myself I was hiding from, and heal it. It was time for a change.

Less than a month later my operatic career came full circle. I had reluctantly agreed to sing Maddalena in Rigoletto with Maestro Anton Coppola. I told him I was too old to sing the role and his snappy reply was, “Oh, so you think I’m too old?” (The maestro is now 86 years old and still going strong.) “You were too busy to do my Amneris, so you’re going to say yes to this.” If you’ve worked with Maestro Coppola you know that this man is an irresistible force to whom you can’t say no. On top of that, no matter how experienced you are, working with the maestro is a masterclass in phrasing.

About halfway through the rehearsal period, I was sitting next to him at break and I said, “I think this is my last opera.” He protested, but in my heart I knew this was it. Rigoletto was my first opera, back in 1970, and now, full circle, it was my last.

As I sat in the green room until Act 4, I felt like someone from another planet who had landed in an unfamiliar world. My colleagues were gossiping about each other’s singing prowess, their lazy agents, their heart-wrenching love affairs, the latest flavor of voice teacher—and for the third time I knew it was time to end my addiction, my 40-year love affair with the stage.

This is the beginning of a dialogue—talk to me

I’ve shared some of my realizations about the difficult decision to leave the stage. Now it’s your turn.